Merry Christmas, Joyeux Noel, Feliz Navidad, Buon Natale, Selamat Natal and all that.

The following video is just a bit of fun. Not to be taken seriously.

"Dilige et quod vis fac." -St. Augustine from the 7th Sermon on the First Letter of St. John.

The following video is just a bit of fun. Not to be taken seriously.

Posted by

Antonio449

at

3:01 AM

0

comments

![]()

Posted by

Antonio449

at

4:23 PM

0

comments

![]()

THE SECOND BOOK OF THE COURTIER

" You all are familiar with those splendid lies so well composed that they move to laughter. A very excellent one was

but lately told me by a friend of ours who never suffers us to be

without them."

Then the Magnifico Giuliano said: "

Be that as it may, it cannot be more excellent or more ingenious

than one which a fellow-Tuscan of ours, a merchant of

Lucca, affirmed the other day as a positive fact." "

Tell it to us," added my lady Duchess.

The Magnifico Giuliano replied, laughing: "

This merchant, so he tells the story, once finding himself in

Poland, decided to buy a quantity of sables with the intention of

carrying them into Italy and making great profit thereby. And

after much effort, being unable to enter Muscovy himself (by

reason of the war that was then waging between the King of

Poland and the Duke of Muscovy), he arranged with the help of

some people of the country, that on an appointed day certain

Muscovite merchants should come with their sables to the frontier

of Poland, and he promised to be there in order to strike the

bargain. Accordingly, proceeding with his companions towards

Muscovy, the man of Lucca reached the Dnieper, which he

found all frozen as hard as marble, and saw that the Muscovites (

who on account of the war were themselves suspicious of the

Poles) were already on the other bank, but approached no

nearer than the width of the river. So, having recognized each

other, the Muscovites after some signalling began to speak with

a loud voice, and to ask the price that they wished for their

sables; but such was the extreme cold that they were not heard,

for before reaching the other bank (where the man of Lucca

and his interpreters were) the words froze in the air, and remained

there frozen and caught in such manner that the Poles,

who knew the custom, set about making a great fire in the very

middle of the river; because to their thinking that was the limit

reached by the warm voice before it was stopped by freezing,

and the river was quite solid enough to bear the fire easily. So, I

when this was done, the words (which had remained frozen for '

the space of an hour) in due course began to melt and to fall in

a murmur, like snow from the mountains in May; and thus they

were at once heard very well, although the men had already

gone. But as the merchant thought that the words asked too

high a price for the sables, he would not accept the offer and so

returned without them."110

56.—Thereupon everyone laughed

Castiglione's original:

Libro Secondo

Quelle belle bugie mo, cosi ben assettate,

come movano a ridere, tutti lo sapete. E quell'amico nostro,

che non ce ne lassa mancare, a questi dì me ne raccontò

una molto eccellente. —

LV. Disse allora il Magnifico JULIANO: Sia come si vuole,

né più eccellente né più sottile non può ella esser di

quella che l'altro giorno per cosa certissima affermava un

nostro Toscano, mercatante lucchese.—Ditela, — soggiunse

la signora DUCHESSA. Rispose il Magnifico JULIANO, ridendo :

Questo mercatante, siccome egli dice, ritrovandosi una volta

in Polonia, deliberò di comperare una quantità di zibellini,

con opinion di portargli in Italia e farne un gran guadagno;

e dopo molte pratiche, non potendo egli stesso in persona

andar in Moscovia, per la guerra che era tra 'l re di Polonia

e 'l duca di Moscovia, per mezzo d'alcuni del paese ordinò

che un giorno determinato certi mercatanti moscoviti

coi lor zibellini venissero ai confini di Polonia, e promise

esso ancor di trovarvisi, per praticar la cosa. Andando

adunque il Lucchese coi suoi compagni verso Moscovia,

giunse al Boristene, il qual trovò tutto duro di ghiaccio come

un marmo, e vide che i Moscoviti, li quali per lo sospetto

della guerra dubitavano essi ancor de'Poloni, erano

già su l'altra riva, ma non s'accostavano, se non quanto era

largo il fiume. Cosi conosciutisi l'un l'altro, dopo alcuni cenni,

li Moscoviti cominciarono a parlar allo, e domandar il

prezzo che volevano dei loro zibellini, ma tanto era estremo

il freddo, che non erano intesi ; perché le parole, prima che

giungessero all' altra riva, dove era questo Lucchese e i suoi interpreti, si gielavano in aria, e vi restavano ghiacciate e prese di modo, che quei Poloni che sapeano il costume, presero per partito di far un gran foco proprio al mezzo del fiume, perché, al lor parere, quello era il termine dove giungeva la voce ancor calda prima che ella fosse dal ghiaccio intercetta; ed ancora il fiume era tanto sodo, che ben poteva sostenere il foco. Onde, fatto questo, le parole, che per spazio d'un'ora erano state ghiacciate, cominciarono a liquefar

si e discender giù mormorando, come la neve dai monti il maggio ; e cosi subito furono intese benissimo, benché già gli uomini di là fossero partiti : ma perché a lui parve che quelle parole dimandassero troppo gran prezzo per i zibellini, non volle accettare il mercato, e cosi se ne ritornò senza. — * LVI. Risero allora tutti.

Posted by

Antonio449

at

8:41 PM

0

comments

![]()

Sebbene s'ha detto "se non è vero è ben trovato" anzi non tutto quello vero è sexy.. . .

Ed altrimenti non tutto quello sexy è vero affatto.

-Gianni Venanzio

Even though it's said: "if it isn't true it's well invented" not everything that's true is sexy.

Furthermore not everything sexy is true either.

Posted by

Antonio449

at

4:46 PM

0

comments

![]()

Also another hilarious episode, this time on the question of AIDS in Africa:

Posted by

Antonio449

at

8:11 PM

0

comments

![]()

L’Adone

Canto Sesto

Il Giardino del piacere

14

Son cinque corpi il cielo e gli elementi

E pur de’ sensi il numero è sì fatto;

L’orbe stellato di bei lumi ardenti

È dela vista un natural ritratto

Son poi tra lor conformi e rispondenti

L’udito al’aere ed ala terra il tatto

Né par che meno in simpatia risponda

L’odorato ala fiamma, il gusto al’onda

Adonis

Canto the Sixth

The Garden of Delights

14

There are five bodies in the heavens and the elements

And the senses are of this same number.

The globe with beautiful burning lights

Is a natural portrait of the sense of sight.

Amongst themselves they are equal and corresponding

The sense of hearing to the air and touch to the earth

Nor does it appear that

Smell to flames and taste to waves

correspond with any less sympathy.

Adonis

Canto Sexto

El jardín de las delicias

14

Hay cinco cuerpos en el cielo y los elementos

Y asimismo los sentidos son de este mismo número

El orbe estrellado por hermosas luces ardientes

Es un retrato natural de la vista

Entonces son entre sí conformes y correspondientes

El oído al aire y el tacto a la tierra

Ni parece que con menos simpatía corresponda

El olfato a la llama y el gusto a las olas.

Posted by

Antonio449

at

4:44 PM

0

comments

![]()

S'i fosse fuoco, arderei 'l mondo;

s'i fosse vento, lo tempestarei;

s'i fosse acqua, i' l'annegherei;

s'i fosse Dio, mandereil' en profondo;

s'i fosse papa, allor serei giocondo,

ché tutti cristiani imbrigarei;

s'i fosse 'mperator, ben lo farei;

a tutti tagliarei lo capo a tondo.

S'i fosse morte, andarei a mi' padre;

s'i fosse vita, non starei con lui;

similemente faria da mi' madre.

Si fosse Cecco com'i' sono e fui,

torrei le donne giovani e leggiadre:

le zoppe e vecchie lasserei altrui.

If I were fire I’d burn the world

If I were wind I’d storm it

If I were water I’d drown it

If I were God I’d sent it to Hell

If I were the Pope I’d be happy

‘cause I would interfere in the life of every Christian.

If I were Emperor I know what I’d do

I’d order everyone’s had cut off like that!

If I were Death I’d visit my father

If I were Life I’d run away from him.

The same thing goes for my mother.

If I were Cecco which I was and am

I’d have young and sprightly women

And the lame and ugly ones I’d leave for another.

Posted by

Antonio449

at

5:48 PM

1 comments

![]()

Here is a meme of my own design. The top ten original (non-parody) Weird Al songs. Meaning there are not direct parodies but have original music and lyrics. Although this doesn't mean the songs are not an indirect parody of an entire musical genre and or song category.

Here they are in reverse order Letterman Style:

10. Albuquerque

9. Good Old Days

8. UHF Theme

7. Good Enough For Now

6. Buy Me A Condo

5. When I Was Your Age

4. Melanie

3. Velvet Elvis

2. You Don't Love Me Anymore

1. One More Minute

Memed: Advise and Dissent, Torgo Devil

Posted by

Antonio449

at

2:13 PM

0

comments

![]()

¿Por qué la grandeza

del sur siempre surge-

el austral, olor a azahar e ingenio?

En cualquier latitud entre pámpano o selva

El encanto del sur sale y nos vence.

Canto del sur que aprendí en la niñez

Párvulos años de leche materna

Pan, agua, y vino

Voz de sabio , voz de poeta

Y las mañas de la lengua,

El mayor laberinto.

Why does greatness always come from the south-

The south wind smelling of orange blossoms and genius?

In any latitude amongst jungle and palm fronds

The enchantment of the south sallies forth and overpowers us.

Song of the south that I learned in my childhood

Tender years of mother’s milk

"Bread, water, and wine"

A wise man's voice and a poet’s

The trickery of language:

The greatest labyrinth.

Posted by

Antonio449

at

4:15 PM

0

comments

![]()

¿Cuántos recuerdos se amontanan

en la cabeza

por el hilo de los días

hasta que el cerebro

se empalaga de musarañas

y viene la muerte callada

por falta de claridad?

How many memories pile up in the head

Throughout the string of days

Until the brain falls pray to cobwebs

And death comes silently

For lack of clarity?

Posted by

Antonio449

at

9:42 PM

0

comments

![]()

Hoy sí, cras non

eso decían los antiguos

Mas tampoco puedo estar del todo seguro

ya que ahora se pudren

En cárceles de polvo y grumo.

Y aunque hablasen de genio y figura

El recuerdo no se capta

Más allá del sepulcro.

Y los muertos

sólo sus penas dejan a la postre,

Y sus huesos.

Lo demás es sobrecarga

Dónde un puente levadizo ciñe

El reino bienaventurado.

Y créeme, de esta raya no pasarás

Hasta dejar el mar de la lujuria

Por rumbos mejores

En que me ames a mí y no mis criaturas.

Y recuerda que todos resucitarán

Mas no todos a la vida

Sino al sueño de la muerte.

English translation:

Today yes, tomorrow no

That’s what our ancestors used to say

But it can’t be all that sure

Since now they’re rotting

In prisons of dust and grime.

Even if they spoke of saving appearances

Memory cannot be grasped

Beyond the gave.

And in the end the dead

Leave their trials behind

Along with their bones

All the rest is dead weight

Where a draw bridge

Closes off the Kingdom of the Blessed.

Believe me, you won’t get beyond this point

Without leaving the sea of lust

For better destinations

Where you love me and not my creatures.

Remember that all will rise

Yet not all to life

But to the dream of death.

Posted by

Antonio449

at

3:48 AM

1 comments

![]()

Posted by

Antonio449

at

6:10 PM

0

comments

![]()

Encerrado pino,

El árbol de la memoria

Envuelto en roca y cristal

Cual avispa en ámbar

Alabastro que savia viva fue

Y el tronco en astillero

donde los anillos las centurias perduran

Cual el loco con su tema.

Posted by

Antonio449

at

3:55 AM

0

comments

![]()

Aún me acuerdo de que en una ocasión, sentado en una eminencia desde la que se dilataba ante mis ojos un inmenso y reposado horizonte, llena mi alma de una voluptuosidad tranquila y suave, inmóvil como las rocas que se alzaban a mi alrededor y de las cuales creía yo ser una, una roca que pensaba y sentía como yo creo que sentirán y acaso pensarán todas las cosas de la tierra, comprendí de tal modo el placer de la quietud y la inmovilidad perpetua, la suprema pereza tal y tan acabada como la soñamos los perezosos, que resolví escribirle una oda y cantar sus placeres desconocidos de la inquieta multitud.

Ya estaba decidido; pero al ir a moverme para hacerlo, pensé, y pensé muy bien, que el mejor himno a la pereza es el que no se ha escrito ni se escribirá nunca. El hombre capaz de concebirlo se pondría en contradicción con sus ideas al hacerlo. Y no lo hice. En este instante me acuerdo de lo que pensé ese día: pensaba extenderme en elogio de la pereza a fin de hacer prosélitos para su religión. Pero, ¿cómo he de convencer con la palabra, si la desvirtúo con el ejemplo? ¿Cómo ensalzar la pereza trabajando? Imposible.

La mejor prueba de mi firmeza en las creencias que profeso es poner aquí punto y acostarme. ¡Lástima que no escriba esto sentado ya en la cama! ¡No tendría más que recostar la cabeza, abrir la mano y dejar caer la pluma!

Posted by

Antonio449

at

12:04 PM

0

comments

![]()

La postrera y negra sombra

Que devora el blanco día

El día que tanto querían los hombres

Sepultados en tinieblas

La primera noche,

la noche eterna

de que brotaron las estrellas

en racimos y colas.

Figuras engastadas en la tabla del universo

fieras que arrastran por los cielos

que ahora el hombre observa

desde el punto solitario de la tierra.

Alacrán y punta en aguijón

Colmillo de jabalí que hiere hasta el hueso

Y cazador que mata sin piedad.

La violencia primera que puebla

Los aires . . .

Todo en suma

Se cifra en negros mares de galaxias

Que congrega el alfabeto universal

El huerto celeste de la fruta prima:

La palabra.

Quisiera volver- dije-,

Volver a la luz más pura

Pues, ¿habrá luz o habrá sombra

desde el borde del olvido?

La no-sombra

la no-luz

más allá de noche y día.

Antes del diluvio de la vista.

El pecado de mirar

y descoser los ojos

ante el asombro de las cosas.

La cosa, átomo último del mundo

Mesa, flor y canto

Las cosas que van llenando

el infraverso del vivir.

Nuestras vidas son las cosas

Envueltas en sombras

Que marcan el fluir de los días.

Los muebles del universo

y el mando perdido entre las almohadas

que buscamos sin esperanza.

Se deliza el destino de entre manos

Sin norte y sin guía

En este mar de tinieblas.

Despierta, lazarillo durmiente,

y avive los sentidos

Mira cómo se pasa la vida

no en horas y en lustros.

Sino en sombras y olvido.

He aquí la postrera sombra,

La raya última del horizonte

Muerto el astro primero

Quizá hay otro sol

por estos cielos

que más brilla,

cuya cúpula dora

el mirar.

Mas entre sombras movemos

y somos

hasta una luz más pura nos eleve.

Y estos, dispersos rasguños

en un charco de papel.

Son testamento, en fin,

De la faena.

Posted by

Antonio449

at

8:52 PM

0

comments

![]()

The militia men shoved him out of his house, ready to make him the 499th martyr for some future beatification. Don Bartolomé let himself be pushed along knowing that he had few hopes. Just the same as always. When he discovered that the leader of the so-called Death Squadron was Manolito from las Tejas he thought maybe all was not lost. He had been Manolito’s teacher in the town’s school and he well knew that the boy’s brute force was matched only by his pride.

“Manolito . . . .” he yelled.

“Name’s Blood, don Bartolomé and I’m not don Manuel either because dons aren't worth a damn any more.”

“Well Don Blood you wouldn’t be planning to kill me, the priest, and the nuns of the Incarnation just like that without convincing us that we’re dying for Freedom and the Revolution?”

“I was thinking ‘don’t put off to tomorrow what you can do today’ like you taught us. The boys are really set on taking you out. The pharmacist and the mayor slipped past us, the damn bastards!”

“But, Manolo, hombre, remember that you are a bunch of (he paused looking around him as if he were lecturing in class) rational animals and you can’t just kill us like that. You have to get the victims to agree with you so that we can happily go on ‘a little walk’ and thank you for your revolutionary work.”

“I am sure I could convince you but not the priest who is so closed minded. Or the nuns who don’t even look at me in the face.”

“Then it’s a deal, Blood, if you convince me you can kill the lot of us,” and he held out his hand.

After that first night in July, Manolo (a.k.a Blood) and don Bartolomé the school teacher discussed political philosophy before the impatient the militia men’s shotguns and the hypersensitive ears of the local cleric. Blood started off like an convincing polemicist despite some and stops and starts. He began to persuade the astonished teacher to the nuns’ chagrin, who dizzyingly followed the twists and turns of the discussion between avemarias.

Don Bartolomé sighed. “Wow, Manolito, collectivization? It had never really dawned on me before.”

And Blood’s chest swelled, it swelled with pride.

Yet just before dawn when the cock crowed Don Bartolomé added, “Why, yes for collectivization we’d be prepared to be executed but all the same, come on! The thing is . . . the Russian Revolution just doesn’t do it for me. It leaves me cold, Blood, that’s all.”

“I have to do more research, Don Bartolomé, so you won’t slip me up by surprise. Also I’m tired. Tomorrow night I’ll convince you in a wink about the greatness of Don José Estalín. Don’t you worry.”

Every night Blood savored the sweet honey of intellectual victory. So much so that he didn’t want any advantage over his opponent. So he allowed the school teacher to return home so he could be near his books for the latest point to be made. The nuns with there hushed speech, distracted them from the debate, and so they returned to the cloister.

And the priest who was for completely closed-off and wouldn’t be persuaded a bit was the only one to stay in the makeshift dungeon they’d set up in the church. The militia men divided into two: those who found pleasure in the nocturnal get togethers and the bohemian lifestyles of intellectuals. And those who got bored and went back to their former agrarian tasks with relief.

A thousand and one nights had not passed but less than half that number when a detachment of the Guardia Civil entered the town. Yet it appeared that in this place they had left War behind. For Blood was dozing off in a wicker chair with Paul Leforgue’s The Right to Laziness between his legs while Don Bartolomé wandered off near the river meditating on collectivization. The guards took down two or three tattered reg flags and opened their mouths wide upon hearing that the Death Squadron was practically a Platonic Dialog.

Before leaving they named new authorities to be put into place. The priest proposed don Bartolomé and don Bartolomé suggested Blood . . . Manolito, I mean.

“Teacher, I think you're crossing the line a bit, hombre,” the captain of the Guardia Civil responded in turn.

Based on the Spanish original by Enrique García-Máiquez published on his blog Rayos y Truenos

499

Los milicianos lo sacaron a empujones de su casa, dispuestos a convertirle en el mártir 499 de una futura beatificación. Don Bartolomé se dejaba empujar, sabiendo que esperanzas tenía pocas. En cambio, esperanza la de siempre. Cuando descubrió que el jefe del autodenominado “Escuadrón de la Canina”, era Manolito, el de las Tejas, pensó que tal vez no estuviese todo perdido. Había sido su profesor en la escuela del pueblo y conocía bien que su fuerza bruta tenía un parangón: su orgullo.

—Manolito…. —gritó.

—Me llamó Sangre, don Bartolomé, y no me llamo don Manuel porque ya no hay dones que valgan…

—Pues don Sangre, ¿no pensarás matarnos a mí y al señor cura y a las monjitas de la Encarnación así como así, sin convencernos de que morimos por la Revolución y por la Libertad?

—Yo pensaba no dejar para mañana lo que puedas hacer hoy, como usted nos enseñó. Los muchachos, ya ve, están deseando darle al gatillo… El boticario y el alcalde se nos han escabullido, los muy maricones…

—Pero, hombre, Manolo, recuerda que sois unos animales (hizo una pausa, mirando en redondo, como si estuviera dando una clase) racionales y que no podéis matarnos sin más, que hay que conseguir que las víctimas os demos la razón, que vayamos tan contentas al paseo, que os agradezcamos de corazón vuestra labor revolucionaria…

—A usted seguro que le podría convencer yo, pero no al cura que es cerril al máximo, y a las monjas, qué, que ni me miran a la cara...

—Trato hecho, Sangre, si me convences a mí, nos das matarile a todos.

Y le tendió la mano.

A partir de aquella noche de julio, en el pueblo, Manolito, alias el Sangre, y don Bartolomé, el maestro-escuela, discutían de filosofía política ante las impacientes escopetas de caza de los milicianos y los hiperestésicos oídos del clero local. Sangre se destapó como un polemista eficaz, a pesar de algún que otro trabucamiento y exabrupto. Iba convenciendo al asombrado maestro, ante el pavor de las monjitas, que entre avemaría y avemaría seguían mareadas los meandros de la discusión. Suspiraba don Bartolomé:

—¡Anda, Manolito!, pues en eso de la colectivización no había yo caído…

Y a Sangre se le esponjaba el pecho. Sólo que un poco antes del alba, cuando avisaban los gallos, don Bartolomé añadía:

—Pues sí, por la colectivización estaríamos dispuestos a ser asesinados, pero ya mismo, vamos... Lo malo es que la Revolución Rusa, no sé, me pilla un poco lejos, Sangre, me deja frío.

—Tengo que documentarme, don Bartolomé, no me va usted a coger por sorpresa… Además estoy cansado. Mañana por la noche le convenzo en un periquete de las bondades de don José Estalín, pierda cuidado.

Sangre saboreaba cada noche las mieles de una victoria intelectual. Tanto, que no quería ventajas sobre su oponente. Así que dejó que el maestro volviese a su casa: que tuviese cerca sus libros para preparar el último, siempre el último, punto pendiente. Las monjas, como con tanto cuchicheo distraían el debate, volvieron a la clausura. Y el cura, que ciertamente era cerril y no se dejaba convencer ni un ápice, fue el único que se quedó en el calabozo que habían improvisado en la iglesia. Los milicianos se dividieron en dos: los que le cogieron gusto a las tertulias nocturnas y a la bohemia de la intelectualidad y los que, aburridos, volvieron aliviados a las labores del campo.

No habían pasado mil y una noches, sino un poco menos de la mitad, cuando un destacamento de la Guardia Civil entró en el pueblo. Allí parecía que la guerra no iba con ellos. Sangre estaba dormitando en una silla de anea con el libro de Paul Laforgue, El derecho a la pereza, entre las piernas; y don Bartolomé andaba por el río, pensando en la colectivización. Los guardias arriaron dos o tres banderas rojas y raídas y abrieron la boca oyendo que el “Escuadrón de la Canina” era, prácticamente, un diálogo platónico.

Antes de irse, tenían que dejar nombradas nuevas autoridades. El cura propuso a don Bartolomé y don Bartolomé a Sangre, quiero decir, a Manolito.

— Hombre, maestro, no se pase —repuso el capitán de la Guardia Civil.

Enrique García-Máiquez enlace al cuento original

Posted by

Antonio449

at

7:53 PM

3

comments

![]()

Walking, walking along

I want to hear each grain of sand

I’m trampling under foot

Walking along,

Leave behind the horses,

For I want to get there late

(walking, walking along)

and give my soul to each grain of sand

that I’m brushing past.

Walking, walking along

What a sweet entrance

You make in the countryside, oh great night, as you descend!

Walking along,

My heart is a backwater

I am already what is in wait for me

(Walking, walking along)

and my hot foot appears

to be kissing my heart

Walking, walking

I want to see the faithful tears

Of the path I’m leaving behind..

ANDANDO

Andando, andando.

Que quiero oír cada grano

de la arena que voy pisando.

Andando.

Dejad atrás los caballos,

que yo quiero llegar tardando

(andando, andando)

dar mi alma a cada grano

de la tierra que voy rozando.

Andando, andando.

¡Qué dulce entrada en mi campo,

noche inmensa que vas bajando!

Andando.

Mi corazón ya es remanso;

ya soy lo que me está esperando

(andando, andando)

y mi pie parece, cálido,

que me va el corazón besando.

Andando, andando.

¡Que quiero ver el fiel llanto

del camino que estoy dejando!

Posted by

Antonio449

at

7:53 PM

0

comments

![]()

Who could know how

To happily leave one’s cloak

In the arms of the past

And not look back at what was

To enter happily and head on

and fully naked, into the free happiness of the present!

(Fragment from Unidad (1918-1923)

¡Quién supiera

dejar el manto, contento

en las manos del pasado

no mirar más lo que fue

entrar de frente y gustoso

todo desnudo, en la libre

alegría del presente!

Posted by

Antonio449

at

7:53 PM

0

comments

![]()

From Neruda's Canto General (V:1):

The Paraná among the tangled, humid and pulsating

Regions of other rivers

the Yabebirí: that web of waters.

And Acaray, Igurey, twin jewels colored

With quebracho and surrounded by the thick branches

Of copal trees,

goes on toward atlantic savannahs

Brushing along the delirium of the purple nazarene,

And the roots of the curupay plant in its sandy dreams.

The hot silt and the thrones of the devoring caiman

Amidst pestilence

Doctor Francia crossed over to the seat of Paraguay

And lived among rose windows

Of pink masonry

Like a sordid, imperial statue

Covered with the veils of the shadowy spider.

Solitary grandeur

In a hall full of mirrors

A frightful figure dressed in black

Over red felt

And fearful rats in the night.

False column,

Perverse academy,

A leperous king’s agnosticism

Surround by vast fields of grass

Drinking platonic numbers

At the condemned man’s gallows.

He calculated triangles in the stars,

measuring stellar coordinates

with a watch

as Paraguay’s orange night approached.

And even during the death throws of

the condemned man seen from his window

he had his hand on the lock of captive twilight.

Study materials strewn on the table

His eyes were fixed on the spir of the firmament

In the shifting crystals of geometry

While the intestinal blood

of the man slain by bayonnet buts

flowed down the stairs,

Drunk up by green swarms of flickering flies.

He closed off Paraguay

Like a nest for his Majesty

He tied torture and mud to its borders

When his siluet passes by the street

The indians glance at the city walls

As his shadow bounces off them

Creating two walls of shivering fear.

When death came to Doctor Francia

He was motionless and dumb

Alone in his cave and

Tied down within himself,

By the ropes of paralysis.

He went through his final agony and died alone

Without anyone entering the room.

For no one dared to knock on the master’s door.

Tied up by these serpents

Speachless and with his brain boiled

He died lost in the solitude of his palace

While night, established like a university chair

Devored the miserable capital columns

Sprinkled with martyrdom

El doctor Francia

El Paraná en las zonas marañosas,

húmedas, palpitantes de otros ríos

donde la red del agua, Yabebirí,

Acaray, Igurey, joyas gemelas

teñidas de quebracho, rodeadas

por las espesas copas del copal,

transcurre hacia las sábanas atlánticas

arrastrando el delirio

del nazaret morado, las raíces

del curupay en su sueño arenoso.

Del légamo caliente, de los tronos

del yacaré devorador, en medio

de la pestilencia silvestre

cruzó el doctor Rodríguez de Francia

hacia el sillón del Paraguay.

Y vivió entre los rosetones

de rosada mampostería

como una estatua sórdida y cesárea

cubierta por los velos de la araña sombría.

Solitaria grandeza en el salòn

lleno de espejos, espantajo

negro sobre felpa roja

y ratas asustadas en la noche.

Falsa columna, perversa

academia, agnosticismo

de rey leproso, rodeado

por la extensión de los yerbales

bebiendo números platónicos

en la horca del ajusticiado,

contando triángulos de estrellas,

midiendo claves estelares,

acechando el anaranjado

atardecer del Paraguay

con un reloj en la agonía

del fusilado en su ventana,

con una mano en el cerrojo

del crepúsculo maniatado.

Los estudios sobre la mesa,

los ojos en el acicate

del firmamento, en los volcados

cristales de la geometría,

mientras la sangre intestinal

del hombre muerto a culatazos

bajaba por los escalones

chupada por verdes enjambres

de moscas que centelleaban.

Cerró el Paraguay como un nido

de su majestad, amarró

tortura y barro a las fronteras.

Cuando en las calles su silueta

pasa, los indios se colocan

con la mirada hacia los muros:

su sombra resbala dejando

dos paredes de escalofríos.

Cuando la muerte llega a ver

al doctor Francia está mudo,

inmóvil, atado en sí mismo,

solo en su cueva, detenido

por las sogas de la. parálisis,

y muere solo, sin que nadie

entre en la cámara: nadie se atreve

a tocar la puerta del amo.

Y amarrado por sus serpientes,

deslenguado, hervido en su médula,

agoniza y muere perdido

en la soledad del palacio,

mientras la noche establecida

como una cátedra, devora

los capiteles miserables

salpicados por el martirio.

Posted by

Antonio449

at

10:19 PM

1 comments

![]()

Dr. José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia y Velasco (January 6, 1766 – September 20, 1840) was the first leader of Paraguay following its independence from Spain. He ran the country with no outside interference and little outside influence from 1814 to 1840.

Born in Yaguarón, he became a doctor of theology and trained for the Catholic priesthood but never entered it. When Paraguay's independence was declared in 1811, he was appointed secretary to the national junta or congress. He was one of the few men in the country with any significant education, and soon became the country's real leader.

In 1814, a congress named him Consul of Paraguay, with absolute powers for three years. At the end of that term, he sought and received absolute control over the country for life. For the next 26 years, he ran the country with the aid of only three other people. He aimed to found a society on the principles of Rousseau's Social Contract and was also inspired by Robespierre and Napoleon. To create such a personal utopia he imposed a ruthless isolation upon Paraguay, interdicting all external trade, while at the same time he fostered national industries. He became known as a caudillo who ruled through ruthless suppression and random terror with increasing signs of madness, and was known as "El Supremo".

He outlawed all opposition and abolished higher education (while expanding the school system), newspapers and the postal service. He abolished the Inquisition and established a secret police force. He had abolished higher education because he saw the need to spend more money in the military in order to defend Paraguayan independence from those that did not recognize it such as Argentina.

..........

Francia later seized the possessions of the Roman Catholic Church, nationalizing the land as communal farms which proved successful. He appointed himself head of the Paraguayan church, for which the Pope excommunicated him.

He made marriage subject to high taxation and restrictions, insisting he personally conduct all weddings. To reduce the influence of the Spanish gentry, he forbade them to marry among themselves.

Quotes:

"The best saints to guard the borders with are cannons."

Note: When the commander of a new fortress asked for permission to put it under the patronage of a saint.

* "Para guardar las fronteras, los mejores santos son los cañones."

o Nota: Cuando el comandante de una nueva fortaleza le pidió permiso para ponerla bajo la advocación de un santo.

"If someone walking on the street stops and looks at my house's facade, fire on him. And you if you miss shoot again and if you still miss your mark, I'm sure my pistol will not err."

Note: To a centry that let a woman peer through window at the furniture inside one of the rooms of the Dictator's Palace.

* "Si alguno de los que pasen por la calle se detuviere, fijándose en la fachada de mi casa, haz fuego sobre él; si lo yerras, haz otro tiro, y si todavía lo yerras, ten por seguro que mi pistola no ha de errarte."

o Nota: A un centinela que había tolerado a una mujer que mirase por una ventana los muebles de una de las habitaciones de Palacio.

"If the pope were to come to Paraguay, maybe I'll name him my chaplain but he's better off in Rome and me in Asuncion."

* "Si el Papa viniera al Paraguay, puede ser que le nombrara mi capellán, pero bien se está él en Roma y yo en La Asunción."

(Wikipedia)

Posted by

Antonio449

at

11:39 PM

0

comments

![]()

Segunda Sombra

Pasado el crepúsculo camino a noche

El orbe gira en su compás

Y hiela el frío de los astros

Primera noche de oscuridad

Y arrasada estrella,

Cuévano del espacio

y tumba de los años luz.

Término de toda órbita

Detrás del común mirar

Del que huye la materia

En estrepitosa carrera

Para acabar absorbida,

en la manga de la noche.

Sol mortecina,

Apagada mechera

El fuego solar derretido en

Partículas elementales

Que atraviesan el tiempo.

Si mañana hubiera acaso

Otro gallo cantaría

Mas por falta del pajarraco y su día

sólo hay mudos astros

Que callan su secreto:

El enigma de lo pesado.

Pesada la vida que se pasa en silencio

El silencio que mide el tiempo y su pesar

El peso es centro

De dónde dista cuerpo y tomo.

Es la forma de las sombras,

Huellas de luz

Que hurtan

Y no perdonan

Posted by

Antonio449

at

7:41 AM

0

comments

![]()

Primera sombra

Sombra de sauce,

De trébol y de pez,

rastros de vida que se notan

Tras el llorar y obrar.

Hay chispas de tinieblas.

Que navegan sin cesar

Por los surcos del mar nocturno.

Negra sombra y plaga del ver,

Sombra que ocultas y no revelas,

¿Cuál será la muerte que encubres

En el silencio de las horas?

Cuando el día se retira en tinieblas

Y las sombras crecen.

Vuelta del trabajo

Camino lento

El sol a las espaldas

Que se mengua cual la luna

En un lecho de fuegos artificiales

Senderos de nácar bajo un sol que muere

De hito en hito los rayos se deluyen

De blanco claro en púrpura fúnebre.

Allá lo encierran en un cajón de plata y carmesí

Para nunca más volver.

Nunca más volver . . . . .

Posted by

Antonio449

at

1:44 PM

0

comments

![]()

In 1593 Luis de Góngora was a deacon at the Cathedral of his native Córdoba. Although he had previously been censured for writing profanes lyrics and poetry the archbishop continued to send him to other dioceses at his own behest. During one of these trips to his alma mater Salamanca he suffered a seizure or stroke and slipped into a coma. His experience during this illness would mark the beginning of his mysterious, long poem The Solitudes. These are two sonnets he wrote after his recovery:

About an ill wayfarer who fell in love in the place where he stopped to rest.

A lost and sickly pilgrim

In the midst of a dark night with stumbling gait

Crossed the confusion of the desert

and with uneven steps he called out in vain.

He heard the repeated barking

Of an awakened but faraway dog

And found charity, if not the way home,

in a shepherd’s badly roofed shelter

The sun came out

And hidden among mink furs

The sleeping beauty startled

The ill wayfarer with sweet rage.

He will pay for such hospitality with his life

And it would be better for him to wander the mountains

Than perish the way I do now.

(1594)

DE UN CAMINANTE ENFERMO QUE SE ENAMORÓ DONDE FUE HOSPEDADO

Descaminado, enfermo, peregrino

En tenebrosa noche, con pie incierto

La confusión pisando del desierto,

Voces en vano dio, pasos sin tino. Repetido latir, si no vecino,

Distincto oyó de can siempre despierto,

Y en pastoral albergue mal cubierto

Piedad halló, si no halló camino.

Salió el sol, y entre armiños escondida,

Soñolienta beldad con dulce saña

Salteó al no bien sano pasajero.

Pagará el hospedaje con la vida;

Más le valiera errar en la montaña,

Que morir de la suerte que yo muero.

This sonnet has several illusions which must be explained. The Torme is the river that runs through Salamanca. And Lazarillo de Tormes was a character from the precursor of all Picaresque Novels. The boy Lazarillo has various masters after the demise of his parents. The first of which is a blind beggar. In Spanish lazarillo- 'means a guide for the blind' This master of his was very cruel to the boy so he took revenge on him before leaving his service. Lazarillo is also a variation of the name Lazaro the Spanish form of Lazarus, Jesus' friend whom He brought back to life.

The river Tormes had me for dead near its shores

In a deep catatonic slumber

When Golden Sir Apollo

Thrice released his horses

My resurrection was a miracle

Like Lazarus’ return to the world

So I am already reckoned as Castile’s second

Lazarillo de Tormes.

I entered the service of a blind man

My soul held lifeless in a sweet fire

That’ll reduce me to ashes.

How fortunate I would be then

If I imitated Lazarillo one day

In the revenge he took on the blind beggar!

(1593-4)

Muerto me lloró el Tormes en su orilla,

En un parasismal sueño profundo,

En cuanto don Apolo el rubicundo

Tres veces sus caballos desensilla.

Fue mi resurrección la maravilla

Que de Lázaro fue la vuelta al mundo,

De suerte que ya soy otro segundo

Lazarillo de Tormes en Castilla.

Entré a servir a un ciego, que me envía,

Sin alma vivo, y en un dulce fuego,

Que ceniza hará la vida mía.

¡Oh qué dichoso que sería yo luego,

Si a Lazarillo le imitase un día

En la venganza que tomó del ciego!

Posted by

Antonio449

at

12:42 AM

0

comments

![]()

Sonnet

I have seen strange things, my Celalba,

clouds breaking open, winds running wild

High towers brought down to their foundations

And the earth vomit up its depths.

Strong bridges breaking like weak straws

Great streams, violent rivers

Not forded enough by thought

And worse detained by mountains.

Noah’s people, atop high pines

I saw shepherds, dogs, huts, and cattle

in the water lifeless and without form

And I feared nothing but my own thoughts.

Soneto.

Cosas, Celalba mía, he visto extrañas:

cascarse nubes, desbocarse vientos,

altas torres besar sus fundamentos

y vomitar la tierra sus entrañas;

duras puentes romper, cual tiernas cañas,

arroyos prodigiosos, ríos violentos,

mal vadeados de los pensamientos

y enfrenados peor de las montañas;

los días de Noé, gentes subidas

en los más altos pinos levantados,

en las robustas hayas más crecidas.

Pastores, perros, chozas y ganados

sobre las aguas vi, sin forma y vidas,

y nada temí más que mis cuidados.

Posted by

Antonio449

at

10:54 AM

0

comments

![]()

I go to and from my solitudes.

And walking off by myself

My thoughts are enough for me.

I don’t know what the village has

where I live and and where I die

But I can’t go any further

Than from myself.

As for me, I am neither good or bad

But something tells me that he who is all soul

Is still trapped in his body.

I understand what is enough for me

But what I don’t understand

Is how an ignorant prideful man

Can stand himself.

Of all the things that tire me

I can easily defend myself

Yet I can’t guard myself

From the dangers of the fool.

He will say that I am one too

But with false arguments

For humility and foolishness

Cannot fit together in one man.

I know the difference

For in him I see

His madness and arrogance

And in me

humility in my self-hatred

Nature knows more than

Is found out in this time

For many who are born wise

It’s only because they say it’s so.

“I only know that I no nothing”

a philosopher said, making known his humility

where more is less.

I do not esteem myself as wise

But as unfortunate

For those who are not fortunate

How can they be discrete?

The world cannot last long

For as they say and I believe it to be so-

it is like a cracked glass

That will soon shatter.

These are signs of judgment-

Seeing that we are all losing this game

Some for too many cards

And others for not having enough.

They say that long ago the Truth left for the heavens

Thus had man placed her in his esteem

And she has not returned since.

We live in two ages

Our own and someone else’s

Silver is ours

And copper that of our neighbor.

Who would not be worried

-If he be a good Spaniard-

Seeing men in olden times

And valor in a modern state?

Everyone goes around well dressed

And complains about prices-

Romans from the waist up

And Pilgrims from the waist down.

God said that man would first eat his bread

By the sweat of his brow

For breaking His commandment.

And some inobedient

Out of shame and fear

Have switched the effects

for the articles of their honor.

Virtue and philosophy wander like blind men

One after the other

They go along crying and begging.

The world has two poles,

One single movement,

Favor for the best life

And money for the best blood.

I hear the bells ring

And it doesn’t surprise me though it could

That in place of so many crosses

There be so many dead men.

I am peering at the graves

Whose marble works though eternal

Are saying without tongues

That their owners were indeed not.

Blessed be he who made them!

For only through them

Did the lowly have vengeance

On the great and the powerful.

They paint Envy as ugly

I confess that I feel it

For some people

Who don’t know

Anyone who lives amongst walls.

Without book and papers

Treaties, accounts, or stories

When they wish to write

They borrow an inkwell.

Without being rich or poor

They have a chimney and garden

Worries don’t wake them

Or wranglings and pretensions.

Nor do they murmur against the great

Or offend the lowly

Nor do they ever – unlike me-

Sign an I–O-U

Or give out holiday cards.

So with this envy of which I speak

And what I pass over in silence

I go to and from my solitudes.

(From the Dorotea, 1632)

A mis soledades voy,

de mis soledades vengo,

porque para andar conmigo

me bastan mis pensamientos.

No sé qué tiene el aldea

donde vivo y donde muero,

que con venir de mí mismo,

no puedo venir más lejos.

Ni estoy bien ni mal conmigo;

mas dice mi entendimiento

que un hombre que todo es alma

está cautivo en su cuerpo.

Entiendo lo que me basta,

y solamente no entiendo

cómo se sufre a sí mismo

un ignorante soberbio.

De cuantas cosas me cansan,

fácilmente me defiendo;

pero no puedo guardarme

de los peligros de un necio.

Él dirá que yo lo soy,

pero con falso argumento;

que humildad y necedad

no caben en un sujeto.

La diferencia conozco,

porque en él y en mí contemplo

su locura en su arrogancia,

mi humildad en mi desprecio.

O sabe naturaleza

más que supo en este tiempo,

o tantos que nacen sabios

es porque lo dicen ellos.

«Sólo sé que no sé nada»,

dijo un filósofo, haciendo

la cuenta con su humildad,

adonde lo más es menos.

No me precio de entendido,

de desdichado me precio;

que los que no son dichosos,

¿cómo pueden ser discretos?

No puede durar el mundo,

porque dicen, y lo creo,

que suena a vidrio quebrado

y que ha de romperse presto.

Señales son del juicio

ver que todos le perdemos,

unos por carta de más,

otros por carta de menos.

Dijeron que antiguamente

se fue la verdad al cielo;

tal la pusieron los hombres,

que desde entonces no ha vuelto.

En dos edades vivimos

los propios y los ajenos:

la de plata los estraños,

y la de cobre los nuestros.

¿A quién no dará cuidado,

si es español verdadero,

ver los hombres a lo antiguo

y el valor a lo moderno?

Todos andan bien vestidos,

y quéjanse de los precios,

de medio arriba romanos,

de medio abajo romeros.

Dijo Dios que comería

su pan el hombre primero

en el sudor de su cara

por quebrar su mandamiento;

y algunos, inobedientes

a la vergüenza y al miedo,

con las prendas de su honor

han trocado los efectos.

Virtud y filosofía

peregrinan como ciegos;

el uno se lleva al otro,

llorando van y pidiendo.

Dos polos tiene la tierra,

universal movimiento,

la mejor vida el favor,

la mejor sangre el dinero.

Oigo tañer las campanas,

y no me espanto, aunque puedo,

que en lugar de tantas cruces

haya tantos hombres muertos.

Mirando estoy los sepulcros,

cuyos mármoles eternos

están diciendo sin lengua

que no lo fueron sus dueños.

¡Oh, bien haya quien los hizo!

Porque solamente en ellos

de los poderosos grandes

se vengaron los pequeños.

Fea pintan a la envidia;

yo confieso que la tengo

de unos hombres que no saben

quién vive pared en medio.

Sin libros y sin papeles,

sin tratos, cuentas ni cuentos,

cuando quieren escribir,

piden prestado el tintero.

Sin ser pobres ni ser ricos,

tienen chimenea y huerto;

no los despiertan cuidados,

ni pretensiones ni pleitos;

ni murmuraron del grande,

ni ofendieron al pequeño;

nunca, como yo, firmaron

parabién, ni Pascuas dieron.

Con esta envidia que digo,

y lo que paso en silencio,

a mis soledades voy,

de mis soledades vengo.

(La Dorotea, 1632)

Posted by

Antonio449

at

10:29 PM

2

comments

![]()

The footsteps of a wandering pilgrim

Some lost and others inspired,

Lines that the Sweet Muse dictated to me

In confused solitude . . . . .

(Preliminary verses of the Solitudes)

Pasos de un peregrino son, errante,

Cuantos me dictó versos dulce Musa

En soledad confusa,

Perdidos unos, otros inspirados . . .

(Dedicatoria)

---------------------------------------------------------

Oh most fortunate refuge at any hour.

Pallas’ temple, Flora’s dwelling,

Not of modern hands.

The designs erased, the model was sketched

in keeping with the concave of the heavens.

The sublime building

Your materials are poor

Where the goatherd keeps

Innocence instead of steel.

And the whistle for his livestock.

Most fortunate refuge at any hour!

Ambition doesn’t dwell in thee, chasing after wind.

Food for the Egyptian asp.

Not what starts out with a human face

And ends up being a deadly beast

A capricious sphinx

That makes Narcissus go after echoes

And despise springs.

Nor does it waste gun powder

in impertinent warning shots

when it is most needed.

A profane ritual

That rustic sincerity mocks

Over a curved shepherds staff.

Most fortunate refuge at any hour!

Flattery ignores your threshold

That siren of palaces

Whose sands so many ships have kissed

Sweet trophies of a chanting dream.

Here Pride is not bronzing the feet of Lies

Through the sphere of its feathers

Nor do wax wings fall into foam

because the Sun's rays.

Oh most fortunate refuge at any hour!

«¡Oh bienaventurado

Albergue a cualquier hora,

Templo de Pales, alquería de Flora!

No moderno artificio

Borró designios, bosquejó modelos,

Al cóncavo ajustando de los cielos

El sublime edificio;

Retamas sobre robre

Tu fábrica son pobre,

Do guarda, en vez de acero,

La inocencia al cabrero

Más que el silbo al ganado.

¡Oh bienaventurado

Albergue a cualquier hora!

»No en ti la ambición mora

Hidrópica de viento,

Ni la que su alimento

El áspid es gitano;

No la que, en bulto comenzando humano,

Acaba en mortal fiera,

Esfinge bachillera,

Que hace hoy a Narciso

Ecos solicitar, desdeñar fuentes;

Ni la que en salvas gasta impertinentes

La pólvora del tiempo más preciso:

Ceremonia profana

Que la sinceridad burla villana

Sobre el corvo cayado.

¡Oh bienaventurado

Albergue a cualquier hora!

»Tus umbrales ignora

La adulación, Sirena

De reales palacios, cuya arena

Besó ya tanto leño:

Trofeos dulces de un canoro sueño,

No a la soberbia está aquí la mentira

Dorándole los pies, en cuanto gira

La esfera de sus plumas,

Ni de los rayos baja a las espumas

Favor de cera alado.

¡Oh bienaventurado

Albergue a cualquier hora!»

Posted by

Antonio449

at

3:53 AM

0

comments

![]()

Góngora's Solitudes (Las Soledades) circa 1613

Info:

'The Soledades' ' was going to be a poem in silvas, divided in four parts, corresponding each one allegorically to an age of human life and to a season of the year, and would be called: Solitude of the Country, ' ' Solitude of the Shores, ' ' Solitude of the Forests' ' and ' ' Solitude of the Desert'.

Góngora dedicated the first two poems to the Duke of Béjar and left the second one unfinished. The last 43 verses were added some time later. The stanza style was not new, but it was the first time it was applied to a so extensive poem. Its form, or non stanza-like character, gave more freedom to the poet. So it approached the free verse more and made poetic advances that would only be reached by French Symbolist Poestry in the 19th century.

The plot of the First Solitude is rather conventional, although it is inspired by an episode of The Odyssey, the one about Nausicaa: a young shipwreck arrives at a coast and is rescued by goatherds. But this plot is only a pretext for an authentic descriptive frenzy: the value of the poem is more lyrical than narrative, as indicated by Dámaso Alonso, although more recent studies vindicate the poem's narrative structure. Góngora offers a vision of natures as a new Arcadia, where everything is wonderful and where man can be happy, aesthetically purifying his vision. Which is nevertheless rigorously materialistic and epicurean (it tries to impress the senses of the body, not only the spirit), to make all ugly and the disagreeable sensations disappear.

In this manner, by means of allusion, and periphrasis the poet can soften an ugly and disagreeable word (such as cured meat which is transformed into "purple threads of fine grain" (purpúreos hilos de grana fina) and table cloths are referred to as spun snow (nieve hilada), for example).

Translation:

The country man

Making the mountain an easy plain

Attentively follows the stone,

Beautiful despite the darkness

Bright despite the stars.

An indignant tiara

If apocryphal traditions don’t lie

Of a dark animal whose forehead

Is the brilliant chariot of nocturnal day.

The young man diligently

Speeds up his pace

Measuring the thickness of the brush

With the same foot.

Fixed- despite the cold fog-

On the diamond, his needle’s True North

Or the stars are growling or the tree grove crunches

The watch dog ever vigilant

Greets the wayfarer and then departs.

And what from far off seemed like a small light

Is immense up close.

The robust oak tree lies within it

Like a moth, becoming ash in its flame.

Original:

Cual, haciendo el villano

La fragosa montaña fácil llano,

Atento sigue aquella

—Aun a pesar de las tinieblas bella,

Aun a pesar de las estrellas clara—

Piedra, indigna tïara

—Si tradición apócrifa no miente—

De animal tenebroso cuya frente

Carro es brillante de nocturno día:

Tal, diligente, el paso

El joven apresura,

Midiendo la espesura

Con igual pie que el raso,

Fijo —a despecho de la niebla fría—

En el carbunclo, Norte de su aguja,

O el Austro brame o la arboleda cruja.

El can ya, vigilante,

Convoca, despidiendo al caminante;

Y la que desviada

Luz poca pareció, tanta es vecina,

Que yace en ella la robusta encina,

Mariposa en cenizas desatada.

Posted by

Antonio449

at

9:22 PM

0

comments

![]()

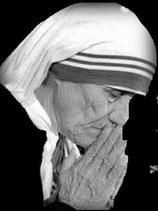

Thus besides His working and loving, the tenderness and afection of his heart, and His lovely care and dedication. The fire and direction of His will with which he always directs his works of love for us, goes beyond anything that can be imagined or said. There is no one so caring, no spouse so mild, no heart so tender and overcome with love nor any kind of friendship so fine that reaches or equals it. For before we love Him He loves us. Offending and despising Him He search us out. Nor can my blindness or stubborn hardness of heart outdo the burning gentleness of His sweet mercy. He wakes up early while we sleep unaware of the dangers that threaten us. He rises early before the dawn. Rather, He neither sleeps nor rests but grasping the door knocker of our hearts He raps all hours at the door and says, as it is written in the Song of Songs: Open up, my sister, friend, and wife. Open up for my head is covered with dew, the locks of my hair are drenched with the raindrops of the night. For He who guards Israel- as David says- does not sleep or become drowsy.

Truly this is what Love is in divinity for as St. John saith: God is Love. So also in the Humanity He took on from us He is love and gentleness. Like the Sun which is the source of light, all that it ever does is shine, sending out rays of clear light form itself without ceasing. Thus also is Christ who is as a fount of love that never runs out always running over with love. This same fire is always brewing in his face and figure. And throughout His dress and person are flames which pass to our eyes. All are rays of love when He appears.

That is why when He first revealed Himself to Moses He showed him only some flames burning in a bramble as if to represent Himself and ourselves in the uncouthness of our thorns and the living, burning love of His heart. Showing in visible appearance the fierce fire he had within His breast for love of His people.

(Fray Luis de León, On the Names of Christ. Shepherd)

Así que, demás de que todo su obrar es amar, la afición y la terneza de entrañas, y la solicitud y cuidado amoroso, y el encendimiento e intensión de voluntad con que siempre hace esas mismas obras de amor que por nosotros obró, excede todo cuanto se puede imaginar y decir. No hay madre así solicita, ni esposa así blanda, ni corazón de amor así tierno y vencido, ni título ninguno de amistad así puesto en fineza, que le iguale o le llegue. Porque antes que le amemos nos ama; y, ofendiéndole y despreciándole locamente, nos busca; y no puede tanto la ceguedad de mi vista ni mi obstinada dureza, que no pueda más la blandura ardiente de su misericordia dulcísima. Madruga, durmiendo nosotros descuidados del peligro que nos amenaza. Madruga, digo: antes que amanezca se levanta; o, por decir verdad, no duerme ni reposa, sino asido siempre al aldaba de nuestro corazón, de continuo y a todas horas le hiere y le dice, como en los Cantares se escribe: «Ábreme, hermana mía, amiga mía, esposa mía, ábreme; que la cabeza traigo llena de rocío, las guedejas de mis cabellos llenas de gotas de la noche.» «No duerme, dice David, ni se adormece el que guarda a Israel.»

Que en la verdad, así como en la divinidad es amor, conforme a San Juan: «Dios es caridad», así en la Humanidad, que de nosotros tomó, es amor y blandura. Y como el sol, que de suyo es fuente de luz, todo cuanto hace perpetuamente es lucir, enviando, sin nunca cesar, rayos de claridad de sí mismo, así Cristo, como fuente viva de amor que nunca se agota, mana de continuo en amor, y en su rostro y en su figura siempre está bulliendo este fuego, y por todo su traje y persona traspasan y se nos vienen a los ojos sus llamas, y todo es rayos de amor cuanto de Él se parece.

Que por esta causa, cuando se demostró primero a Moisés, no le demostró sino unas llamas de fuego que se emprendía en una zarza: como haciendo allí figura de nosotros y de sí mismo, de las espinas de la aspereza nuestra y de los ardores vivos y amorosos de sus entrañas, y como mostrando en la apariencia visible el fiero encendimiento que le abrasaba lo secreto del pecho con amor de su pueblo.

(Fray Luis de León, De los nombres de Cristo. Pastor)

Posted by

Antonio449

at

4:07 AM

0

comments

![]()

One could say that we embrace moral imperatives like a weapon meant to simplify our lives by eliminating huge portions of the world. Nietzsche with his sharp gaze had already identified forms and products of resentment in certain moral attitudes. Nothing that comes out of this can be pleasant. Resentment emanates from a conscience of inferiority. It's the imaginary elimination of he whom we can't really get rid of by our own strength. So in our imagination the person we are resentful toward takes on the livid form of a cadaver, we've already killed him and annihilated with our thoughts. And upon finding him alive and well in the real world he appears to us like an incompliant corpse who is stronger than our powers. His existence is a personified joke on us and a living disdain for our week condition.

A wiser type of this "anticipated death" that the resentful party grants his enemy consists in letting oneself be penetrated by a moral dogma. By which we inebriate ourselves via a certain idea of heroism and come to believe that our enemy has not a speck of reason, or a shred of rights.

(Ortega y Gasset, José. Meditations on Don Quixote: Prologue to the Reader. 1914)

Diríase que abrazamos el imperativo moral como un arma para simplificarnos la vida aniquilando porciones inmensas del orbe. Con aguda Mirada ya había Nietzsche descubierto en ciertas actitudes morales formas y productos de rencor. Nada que este provenga puede sernos simpático. El rencor es una emanación de la conciencia de inferioridad. Es la supresión imaginaria de quien no podemos con nuestras fuerzas realmente suprimir. Lleva en nuestra fantasía aquel por quien sentimos rencor, el aspecto lívido de un cadáver; lo hemos matado, aniquilado con la intención. Y luego al hallarlo en la realidad firme y tranquilo, nos parece un muerto indócil; más fuerte que nuestros poderes, cuya existencia significa la burla personificada, el desdén viviente hacia nuestra débil condición.

Una manera más sabia de esta muerte anticipada que da a su enemigo el rencoroso, consiste en dejarse penetrar de un dogma moral, donde alcoholizados por cierta ficción de heroísmo, lleguemos a creer que el enemigo no tiene ni un adarme de razón ni una tilde de derecho.

(Ortega y Gasset, José. Meditaciones del Quijote: Prólogo al lector. 1914)

Posted by

Antonio449

at

6:59 AM

0

comments

![]()

De un caminante enfermo que se enamoró

donde fue hospedado

Descaminado, enfermo, peregrino,

en tenebrosa noche, con pie incierto

la confusión pisando del desierto,

voces en vano dio, pasos sin tino.

Repetido latir, si no vecino,

distinto, oyó de can siempre despierto,

y en pastoral albergue mal cubierto,

piedad halló, si no halló camino.

Salió el Sol, y entre armiños escondida,

soñolienta beldad con dulce saña

salteó al no bien sano pasajero.

Pagará el hospedaje con la vida;

más le valiera errar en la montaña

que morir de la suerte que yo muero.

Concerning an ailing wayfarer

who fell in love where he was lodged

Misguided, suffering, itinerant

in gloomy night, with indecisive foot

the labyrinth traversing of the wilds,

he called in vain, his steps at random took.

Repeated barking, if not close at hand,

at least distinct, he heard of wakeful dog,

and in a shepherd's cottage, poorly thatched,

compassion found, if not the way he sought.

The sun rose, and beneath her ermine cloak,

a sleepy beauty with sweet savagery

ambushed the traveler so beset with ills.

His lodging he will pay for with his life;

he'd have been better off roaming the hills

than dying in the manner that I die.

(©Alix Ingber, 1995)

Posted by

Antonio449

at

11:07 PM

1 comments

![]()

I have just returned from a conference in Montreal after defending my dissertation, and have just finished moving to a new apartment to stop my job at Ohio Wesleyan so I have not written for a while. But I have just finished reading a nice little book A Hero of Our Time by Mikhail Lermontov, a Russian poet and near contemporary of Pushkin. It is a short novel set in the Caucasus like the picture above. Composed of various narratives concerning an unfeeling Russian dandy. However, Lermontov like Pushkin died in a duel. Here is an eerily prescient poem he wrote shortly before dying:

The Dream

In noon's heat, in a dale of Dagestan

With lead inside my breast, stirless I lay;

The deep wound still smoked on; my blood

Kept trickling drop by drop away.

On the dale's sand alone I lay. The cliffs

Crowded around in ledges steep,

And the sun scorched their tawny tops

And scorched me -- but I slept death's sleep.

And in a dream I saw an evening feast

That in my native land with bright lights shone;

Among young women crowned with flowers,

A merry talk concerning me went on.

But in the merry talk not joining,

One of them sat there lost in thought,

And in a melancholy dream

Her young soul was immersed -- God knows by what

And of a dale in Dagestan she dreamt;

In that dale lay the corpse of one she knew;

Within his breast a smoking wound shewed black,

And blood coursed in a stream that colder grew.

Posted by

Antonio449

at

12:11 AM

0

comments

![]()

Julio se agosta.

Translation:

Today

July is Augusting.

The Spanish se agosta is a coinage coming from an invented verb agostarse "to become August". This new verb in turn sounds like angosto, an adjective meaning wide or angostarse- "to widen out'. Not to mention the more common verb agotarse which when conjugated is: se agota- "is running out" The 's' in se agosta is often aspirated becoming an 'h' sound or silent which makes it sound almost identical to se agota above. Again this play of words works on many levels. This was posted by a poet and blogger from Southern Spain.

(http://egmaiquez.blogspot.com)

Posted by

Antonio449

at

11:30 PM

0

comments

![]()

Viy (Russian: Вий) is a horror story by the Russian-Ukrainian writer Nikolai Gogol, first published in the first volume of his collection of tales entitled Mirgorod (1835).

Gogol opens the story asserting that he is retelling it exactly as he heard it. The story concerns three students from the Bratsky Monastery at Kiev. At the seminary, there are four types of students; the grammarians (freshmen), rhetoricians (sophomores), philosophers (juniors) and theologians (seniors). Every summer after classes have ended, there is usually a large procession of all the students moving around the area as they travel home, getting progressively smaller as each student arrives at his home. Eventually the group is reduced to three students, the theologian Khaliava, the philosopher Khoma Brut and the rhetorician Tibery Gorobets.

As the night draws in, the students hope to find a village off the main road where they can find some rest and food. However, they become lost in the wilderness, eventually coming upon two small houses and a farm. An old woman there tells them she has little room and cannot accommodate any more travelers, but eventually agrees to let them stay. The rhetorician is put in the hut, the theologian in an empty closet and the philosopher in an empty sheep’s pen.

At night, the hag comes to Khoma. At first he thinks she is trying to seduce him, but then she draws closer and leaps on his back, and he finds himself galloping with her all over the countryside with a strength he previously never knew. This flight obviously influenced Mikhail Bulgakov's depiction of Margarita's volitation in the novel Master and Margarita. He eventually slows her down by chanting exorcisms out loud, and then rides on her back as punishment. The hag collapses and he finds she has turned into a beautiful girl.

Khoma runs away to Kiev and continues his easy life there, when a rumor reaches his dean that a rich Cossack’s daughter was found crawling home near death, her last wish being for the philosopher to come and read psalms over her corpse for three days after her death.

Although Khoma is uncertain why the girl requested him specifically, the bribed dean orders him to go to the Cossack’s house and comply with her last wish. Several Cossacks bring him by force to the village where the girl lived. When he is shown the corpse, however, he finds it is the witch he overcame earlier in the story. Rumors among the Cossacks are that the daughter was in league with the devil and they tell horror stories about her ways. Therefore, Khoma is reluctant to say prayers over her body at night.

On the first night, when the Cossacks take her body to a ruined church, he is somewhat frightened but calms himself a bit when he lights up more candles in the church to eliminate most of the darkness, other than that above him. As he begins to say prayers, he imagines to himself that the corpse is getting up, but it never does. Suddenly, however, he looks up and finds that the witch is sitting up in her coffin. She begins to walk around, reaching out for someone, and starts to approach to Khoma, but he draws a circle of protection around himself that she cannot cross. She gnashes her teeth at him as he begins to exorcise her, and then she goes into her coffin and flies about the church in it, trying to frighten him out of the circle. Dawn arrives, and he has survived the first night.

The next night similar events occur, but more horrible than before, and the witch calls upon unseen, winged demons and monsters to fly about the church. When the Cossacks find the philosopher in the morning, he is near death, pale and leaning against a wall. He tries to escape the next day but is captured.

On the third night the witch’s corpse is even more terrifying and she calls the demons around her to bring Viy into the church, who can see everything. Khoma realizes that he cannot look at the creature when they draw his long eyelids up from the floor so he can see, but he does anyway and sees a horrible, iron face staring at him. Viy points in his direction and the monsters leap upon him. Khoma is dead from horror. However, they miss the first crowing of the cock and are unable to escape the church when day breaks.

The priest arrives the next day to find the monsters frozen in the windows as they fled the church and the temple is forsaken forever, eventually overgrown by weeds and trees. The story ends with Khoma’s other two friends commenting on his parting and how it was his lot in life to die in such a way, agreeing that he only came to his end because he flinched and showed fear of the demons.

Posted by

Antonio449

at

10:46 PM

1 comments

![]()

Mikhail Bulgakov 1891-1940

The Heart of a Dog (Russian: Собачье сердце, Sobač'e serdce) is a 1925 story by Mikhail Bulgakov.

It features a professor Philip Philippovich Preobrazhensky (his name is derived from the Russian word for "transfiguration") who implants human testicles and a pituitary gland into a stray dog named Sharik. Sharik then proceeds to become more and more human as time passes, picks himself the name Polygraph Polygraphovich Sharikov, makes himself a career with the Soviet bureaucracy the "Moscow Cleansing Department responsible for eliminating vagrant quadrupeds (cats, etc.)", and turns the life in the professor's house (made up of four apartments) into a nightmare until the professor reverses the procedure.

This is an elaborate satire of Soviet life and more specifically the policies meant to deal with the housing shortage where corrupt practices and micromanagement were legion. Something to consider that in the Communist system no one is different than anyone else. We are all equal, being all the same. Yet if everyone is equal the man of talent such as a scientist or writer finds himself in a strange position. Knowing that he is different from everyone else but having to deny this very fact or deal with policies to this effect. This story illustrates how such concepts when consolidated into systems go against what it means to be human. We have the same problem in the US. If this weren't true about Western Society as a whole and only anti-Communist propaganda then it wouldn't be as funny or tragic as it is.

In essence: we can't all be proletariats. Bulgakov never was able to publish this story in the USSR and shortly afterwards he was barred from ever publishing anything again after a few plays he produced which criticized Stalin's purges in the 30's.

But Stalin liked a play he had written so he didn't have him killed but he couldn't leave the country.

The Master and Margarita (Russian: Мастер и Маргарита) is a novel woven about the premise of a visit by the Devil to the fervently atheistic Soviet Union.

The opening sequence of the book presents a direct confrontation between the unbelieving head of the literary bureaucracy, Berlioz (Берлиоз), and an urbane foreign gentleman who defends belief and reveals his prophetic powers (Woland).

Telling Berlioz about his eminent death: “It is too late Annushka has already spilled the oil.”

Rushing to a meeting Berlioz slips on some sunflower oil which Annushka, a housekeeper has spilled on a street corner, and falls under an oncoming streetcar. As a result of which he is decapitated.

This is witnessed by a young and enthusiastically modern poet, Ivan Bezdomniy (Иван Бездомный - the name means "Homeless"). His futile attempt to chase and capture the "gang" and warn of their evil and mysterious nature lands Ivan in a lunatic asylum. Here we are introduced to The Master, an embittered author, the petty-minded rejection of whose historical novel about Pontius Pilate and Christ has led him to such despair that he burns his manuscript and turns his back on the "real" world, including his devoted lover, Margarita (Маргарита). Major episodes in the first part of the novel include Satan's magic show at the Variety Theatre, satirizing the vanity, greed and gullibility of the new rich; and the capture and occupation of Berlioz's apartment by Woland and his gang.

The gang features Woland the visiting foreign professor, Koroviev an ex-choirmaster, and Behemoth a vodka swirling cat who walks on his hind legs.

(Sources Wikipedia and Antonio449)

Posted by

Antonio449

at

9:13 PM

0

comments

![]()